How culpable am I for my own social media addiction?

In his recent essay for the New York Times, Surgeon General Dr. Vivek Murthy writes that the harms of social media “are not a failure of willpower and parents; they are the consequence of unleashing powerful technology without adequate safety measures, transparency or accountability.”

These powerful sentences come at the end of a thorough evaluation of social media and its role in adolescents’ mental health crisis, a crisis that Murthy deems an “emergency.” For him, the solution to this emergency lies with Congress, technology companies, schools, and public health officials. Each of these entities, he argues, needs to take action to protect adolescents from the harms of social media. “Americans need more than words,” he writes. “We need proof.”

I could not help but notice a critical population that Murthy did not call on to take responsibility: The adolescent social media users themselves.

I am one of those. And while Murthy undoubtedly highlights his concern for my peers and me due to the harms of social media, I fear he overlooks the role we have in both creating and combating our own emergency.

Murthy wrote that in the summer of 2023, American adolescents had an average daily social media use of 4.8 hours. Metrics from my phone tell me that over this past summer, I have a daily average of around 5 hours in total on my phone, 1-2 hours averaged on Instagram and another 30 minutes-1 hour lost to Snapchat.

I may be under the national average, but I still feel the tax that my time on social media has on my mental health. I do spend a lot of time thinking about social media, checking for texts from friends or planning an upcoming post. I do feel the urge to use social media more and more with each post on Instagram. I do use social media to forget about my personal problems, a distraction from the stress of reality. I do often try to reduce use of social media without success, ignoring time limits I’ve set for myself. I do become troubled if unable to use social media, having fear of missing out. And I do use social media so much that it has had a negative impact on my studies, delaying or altogether wasting time on homework for time doom-scrolling.

These six confessions are the same six questions that Addiction Center provides “to determine if someone is at risk of developing an addiction to social media.” A “yes” to more than three may indicate the presence of an addiction.

It is not lost on me that this is an addiction, and while whoever initially introduces an addict to the source of their addiction holds some level of culpability, by the time one becomes an addict, only they can wean themselves off. With that in mind, in his bid to get players at the highest levels involved in the search for solutions, the Surgeon General lets the social media consumers of my generation off the hook.

One of his primary measures would be to place warning labels on social media platforms just as tobacco products carry warnings that say: “Smoking Causes Lung Cancer, Heart Disease, Emphysema, And May Complicate Pregnancy.”

Similarly, any social media limits and warnings set by Congress, technology companies, schools, parents, and public health officials will increase adolescents’ awareness of the dangers of social media on mental health, but adolescents will be the ones responsible to change their behavior.

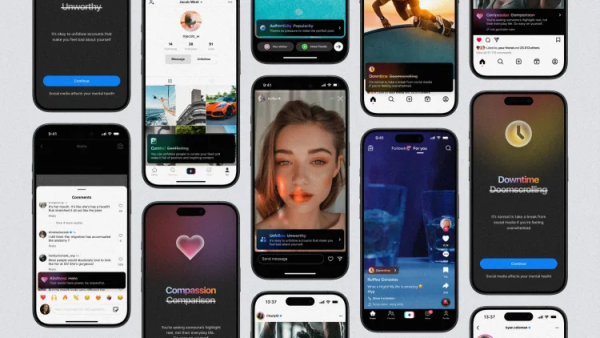

In response to Murthy’s call, Fast Company, a business media brand, invited four creative firms to design “not just [social media] warnings, but interventions that attempt to meet teens where they are without judgment.”

One firm, Metalab, designed badges that appeared after scrolling for an extended amount of time or before commenting and posting, encouraging users to take some downtime, spread kind speech, and present authentic social media curations.

Another firm, PXP Studios, designed a grayscale pop-up that flashes potential risk factors associated with social media, including depression, anxiety, addiction, loneliness, suicidal thoughts, body dysmorphia, reality dysmorphia, reduced self esteem, cyber bullying, sleep disorder, and social isolation.

Essentially, surgeon general warnings like these would operate as small-scale interventions for social media addiction, or, perhaps, small-scale preventions from social media addiction. Murthy highlights that 76% of people in one recent survey of Latino parents said that the warnings would “prompt them to limit or monitor their children’s social media use.”

That said, we must remember it is ultimately the adolescents, not the parents, who will see these warnings and face the subsequent choices. Will we disregard or heed the warnings? Will we exit out of the pop-up or exit the app?

Currently, while a surgeon general warning on social media remains to be seen, adolescents such as myself can set up ScreenTime limits through iPhone settings to control time spent on social media or download free apps like ScreenZen which ask users “Is this important” before opening a social media app.

Sure, as Murthy implores, Congress, technology companies, schools, parents, and public health officials all certainly have their place in regulating social media in order to combat my generation’s mental health crisis, but it is actions like these–opening the apps and abiding to limits–that puts the power in the user.

When drug or alcohol addicts are faced with an intervention, 80-90% agree to get treatment, and a remaining 5-10% agree within the coming weeks, as reported by The Association of Intervention Specialists. However, once in treatment, the American Addiction Center finds that less than 42% of addicts complete the treatment.

Unlike Murthy’s refutation that the harms of social media “are not a failure of willpower,” I believe that the user’s willpower to abide by any present or future social media regulations–to say yes to treatment and to stay in treatment, if you will–is intrinsic to changing behavior on social media for the better.

To turn the Addiction Center’s “yesses” into “nos,” I know that I must begin by saying “yes” to the limits that Murthy calls for and “no” to extended amounts of time on social media. So, perhaps the question is not how culpable am I for my own social media addiction; instead, will I fuel the addiction or stop it?

Charlene Flood • Nov 14, 2024 at 10:52 am

I found Ella Johnson’s piece, Beyond Warnings, to be thoughtful, well-researched, and well-written. She highlights a crucial point about addressing social media addiction that often gets overlooked: while external regulations and interventions are necessary, the individual user’s role is vital. Her willingness to share your reflections on your own social media use is inspiring. Thanks for sharing, Ella!