“I’m not Dylan, Al, you’re Dylan.”

The “Al” whom Bob Dylan corrects is Alan Jules Weberman, the self-titled “Dylanogolist” whose efforts “to enter Bob Dylan’s soul,” as a 1971 Rolling Stone article puts it, went as far as sorting through the garbage can at his private home.

Through obsessive scrutiny of Bob’s lyrics, public statements, and personal trash, Weberman believed he had solved hidden truths about Bob; he believed he knew Bob in a more real way than anyone.

Of course, Weberman’s perceived intimate understanding of Bob’s true self was heavily colored by his own expectations, biases, and desires for Bob to be the type of cultural spokesperson that had solidified his celebrity in the 60s.

But Bob resisted such efforts to dissect his art and life as if he could be boiled down to a single, knowable truth. His response to Weberman—”I’m not Dylan, Al, you’re Dylan”—is both a rejection of the obsessive scrutiny and a wry acknowledgment of how his persona had become a canvas for others’ projections. Bob, the man, refused to be defined by Bob, the myth.

In fact, in the same Rolling Stone article, Bob insists, “really, my poems are very simple. There’s not much there…. I just write poetry. I just write songs. I’m not really that complicated a guy…. My poetry is all very simple…. There’s nothing to my songs but what’s there.” Over and over, whether he’s saying it to the world’s first Dylanolgoist or to countless journalists during interviews and press conferences, Bob rejects the layers of complexity others try to build around him, layers that shape the Bob Dylan people think they know.

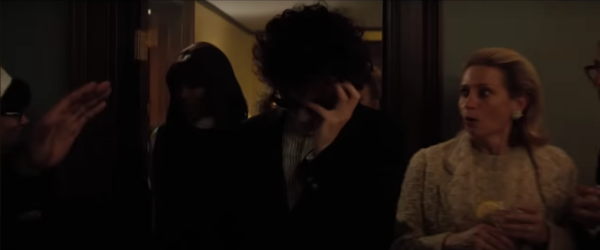

During a striking scene in A Complete Unknown, the Bob Dylan biopic released last month, Bob (played by Timothée Chalamet) complains of a crowded benefit turned gig as he leaves on an elevator: “two hundred people in that room and each one wants me to be somebody else.” Then, as he descends, he speaks on how he manages to perform in spite of this. He says, “I put myself in another place. I’m a stranger there.”

It is here, in the space of strangeness, that Bob steps into a musical realm shrouded in mystique, a mystique that has followed him into his seventh decade of performing and one he himself observed in artists he admired when he first entered the Greenwich Village music scene in the early 60s. In the documentary film No Direction Home, Bob describes this mystique as “something in the eyes that says I know something you don’t.”

Dylan’s work invites interpretation, but it resists conclusion. His cryptic lyrics, shifting identities, and refusal to be pinned down by politics or celebrity speak to the idea that art can—and should—retain a sense of mystery.

Weberman’s fixation on demystifying Bob reveals something universal about the relationship between audiences and artists. There lies a comfort in the illusion that audiences can know the artist behind the art, as if understanding them is the key to decoding their creations. But Bob’s enduring legacy suggests that the opposite is true. The person behind the art does not define the meaning of the creation; art thrives in its ability to remain open-ended.

By doing so, Bob has ensured that his legacy will never be fully understood. Which is the point. By remaining elusive, Bob invites us to see him and his art as eternal, a never-ending reflection of the ever-changing human spirit. In this way, Bob is a kind of Rorschach test: his fans project onto him what they want to see, making his legacy feel deeply personal to everyone who admires him. Even so, Bob’s legacy challenges us not to find answers but to revel in the uncertainty.