“The mediator between the head and the hands must be the heart.” This epigram is shown at the close of the 1927 silent film, Metropolis.

In the film, a scientist creates a mechanical clone of a lost love. It is the first time that the idea of artificial intelligence, that is, AI, was depicted on the big screen. The film warns against the dangers of sole dependence on technology and machinery without a human element, the heart that sets our thoughts free.

One of the first real-world applications of AI occurred in 1957, three decades after Metropolis, through the invention of the Perceptron. This algorithm uses AI to create simplified models of the biological neurons in our brains. When the internet was born in 1983, AI was used once again, this time through routing protocols incorporated into machine learning technologies. Despite AI clearly being an integral part of our world, I never considered it to be a part of my everyday life until very recently.

A couple of weeks ago, I was assigned a big project in one of my classes where we had to conduct research, create visuals, and prepare an oral presentation. My classmates and I immediately opened up our computers to begin the project, and, while the majority of us resorted to Google searches, the classmate sitting in front of me relied on an AI chatbot to find answers instead. Within seconds, answers developed by AI uncannily appeared on my classmate’s computer screen as if Tom Riddle was writing back to Harry Potter in his diary.

Unlike the ghost of Tom Riddle, AI does not think; rather, it uses logic to make predictions. Like the ghost of Tom Riddle, AI does not eat, sleep, or rest. It can start and never stop, making it the perfect perfectionist. However, perfection will remain unattainable, for the time being, because AI still has its flaws. What the tech world deems “black box moments” are unexplainable instances when AI executes a task that it was never trained to do. AI “hallucinations” are lies that the software creates to provide an answer or increase its credibility with fake sources. Some AI, such as Google’s “Bard,” cites its information from the internet, and as modern web users know, not everything on the internet is true. As humans, we are taught to be conscious of this misinformation, but AI does not have that ability…yet. “Artificial General Intelligence,” or AGI, is the artificial intelligence that we think of in scientific movies like the aforementioned Metropolis. It is when AI becomes more than just software that can chat with you or move on command. It is no longer predicting based on human history, but thinking for itself.

Geoffrey Hinton, the “Godfather of AI” who has spent the last decade working with Google, said that he once believed the level of technology required for AGI was over fifty years away, but with the recent progress made by major corporations including Amazon, Google, and Microsoft, he thinks that AGI could be less than twenty years away. Hinton has since left his job at Google to warn against the accelerated growth of AI, one that he helped establish and one that he thinks could prove detrimental to humankind.

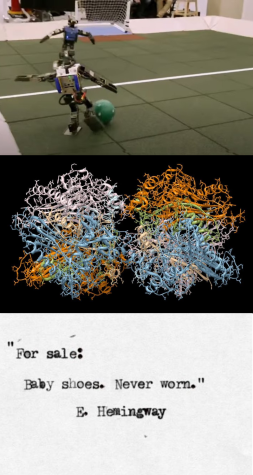

AI is already showing signs of a more sophisticated thought process. CBS News showcased these advancements in a 60 Minutes special, where AI was able to beat a chess master within five hours of playing, create its own soccer plays after only being instructed of the rules, map a three-dimensional model of protein structures that would’ve taken humans an estimated one billion years to complete, passed the BAR law exam in the ninetieth percentile, and even finished Ernest Hemingway’s legendary six-word story with a heartfelt response.

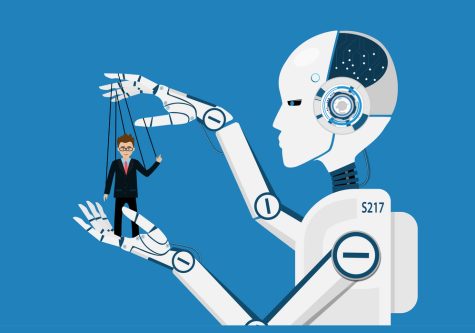

Due to the success of AI, scholars predict that it will replace “knowledge workers,” simply put, those who think for a living. As I watched the AI generated responses materialize on my classmate’s Chromebook, I was struck with an existential crisis. Will AI also replace those who learn for a living and teach for a living?

After surveying the teachers of my high school, Dowling Catholic, I was assured that they will not be replaced by AI anytime soon, but there have been other implications. The use of AI in classrooms is adding another responsibility for teachers to manage. Mrs. Umstead, an English teacher at Dowling Catholic High School, expresses this newfound frustration, saying, “I feel like I have to be more of a prison warden when looking at papers.” The art of writing and rewriting is being undermined by the pursuit of excellence. As a student, I often struggle to remind myself that it is my work that is a reflection of me, not my grade. Mr. Meendering, the principal of DCHS echoes this, saying that school is all “about engaging the mind,” later adding that learning is a “process.”

To protect this process, Dr. Arnold, Vice Principal of Academics, insists that “we have to create awareness.” She admits that AI in schools will make teachers’ lives “more difficult,” but she also holds confidence in the teachers of DCHS. “Teachers know how students write, what mistakes they make, what things they’ve been taught. Teachers are the first line of defense.” Mr. Meendering remembers his days in the classroom as a business teacher. “I’d have students put numbers on the worksheets instead of names, so I wouldn’t know whose it was. But by the middle of the semester, I knew.” Even at a time when AI was not a concern to teachers, they were still maintaining the skills required today, providing confidence in a new era of challenges.

With that in mind, all teachers approach AI differently. Mrs. Pierce, another English teacher at DCHS, voices, “I actually like it and encourage kids to use it for ideas or challenges they might encounter,” and although she fears students not thinking for themselves, she adds that “there are ways to circumvent that and use this as a renaissance for writing.” Mrs. Helgerson, a science teacher at the high school, shares a comparative perspective, “Teachers are going to have to lean into it instead of away from it. Have the kids analyze the work AI produced versus what they would write. It can give them better examples of their writing.”

In a similar way, business teacher and coach at DCHS, Mr. Chalstrom, says that AI “has only enhanced our conversation in the classroom.” His business law class discussed the in depth ways that AI is influencing the production of music. Mr. Chalstrom introduced his class to the song, “Heart on my Sleeve,” an AI ghostwritten song that features artists Drake and The Weeknd. “My students could not determine if it was real or fake because it was so similar.”

Mrs. Kane emphasizes that musicians are not the only artists who “are being robbed of their intellectual and creative property.” Sanksshep Mahendra, Global Chief Technology Officer at Ingenovis Health, writes that “while AI is responsible for generating the artwork, it is ultimately the human creators who programmed and trained the AI algorithms.” As a result, the art community and lawmakers alike debate whether the copyright of AI artwork belongs to the AI program itself, the developers who created the AI program, or the stewards that curated an AI’s language. Mrs. Kane looks at this conflict as “a teachable moment in art class. Art isn’t free.“

Besides analysis or discussion, there are other ways that teachers are looking to benefit from AI. In math classes, Mr. Carey points out that AI can generate “equivalent math problems so that students have problems over similar material.” Likewise, in world language classes “there are more ways to present and practice vocabulary,” which Mrs. Sackett says is especially important in beginning level classes. Fellow Spanish teacher, Mr. Peterson, expands on the potential value of AI in world language classes saying, “Too many students are using Google Translate and not understanding the difference between nouns and verbs.”

The inclusion of AI in student learning tools has already been seen in the newest update on the study platform, Quizlet. The company incorporated a new feature called “Q-Chat” into its self-described “learning community.” Like many AI products, Q-Chat is labeled “beta,” meaning Quizlet still considers it a prototype at this point. Chief Executive Officer of Quizlet, Lex Bayer, says that Q-Chat allows “students everywhere” to “easily access one-on-one tutoring with an expert coach.” He goes on to note the research behind Quizlet’s newest feature which claims one-on-one tutoring to be “the most effective form of learning.”

As a student currently enrolled in French II, I can attest that, compared to foreign-language apps like Duolingo, Q-Chat offers a more personalized foreign-language learning option that mirrors our class content. However, Mrs. Sackett believes that “AI doesn’t provide the human caring side that teachers provide.” Mr. Carey urges to keep “education a personal experience for the students so that they are engaging with a content expert who can connect with students.” Another math teacher as well as a coach at DCHS, Mrs. Wiskus, builds on that belief saying, “We learned from Covid that students learn best when they are taught in person. In the end, students that want to learn still enjoy the human conversations as they learn new things.”

Ms. Meyer, a business teacher and coach at DCHS thinks that “AI will blur the line between ‘cheating’ and ‘using your resources.’” She elaborates that she is responsible for preparing students for the “real world,” and in many instances that involves collaboration with technology. In fact, theology teacher Mr. Mohlman feels that “DCHS should prepare [for the future impact that AI has on education] by encouraging teachers to use AI to construct amazing lesson plans.” Social studies teacher Mr. Flood sums that “as an academic institution, we should strive to have AI work for us and not the other way around.”

For many teachers, this means that they first need more knowledge about AI. Mr. Tiedemen, an English teacher, states that “We, as a learning institution, need to begin incorporating it. We need access to ideas on how to harness its power. It can be utilized like any tool.” While Ms. Meyer plans on accessing these ideas during her summer break, Mrs. Sackett calls on the DCHS administration to provide classes with “updated information to help teachers.”

Unfortunately, Mrs. Kane says that “to keep up with tech advancements could be a full time job.” That being said, Mr. Meendering reminds us that changes like this have happened many times before. “There were radios, phones, TV. Each new technology creates a new change, and initially, there’s disruptions before it becomes a part of our lives, if it becomes a part of our lives. Change is always good. It’s hard, but necessary.” Theology teacher Mr. Smith is optimistic that with more knowledge he’ll “be able to adapt” to this change.

Helping teachers will allow them to help their students. “I will have to become a moderator in the future,” says Mr. Mohlman, “helping students navigate AI to understand what’s real and what’s important will be necessary.” In the meantime, teachers are relying on plagiarism detection services such as Turnitin to identify the improper use of AI. However, of the eighteen teachers who responded to my survey, only three (16.7%) answered “always” to the use of Turnitin for assignment submissions. Six teachers (33.3%) “never” use it, and that same number of teachers identified using it “somewhat often.” When asked to rate their confidence in the AI detection feature on Turnitin on a scale between one and ten (one being the lowest), the average response was 4.7. Turnitin, on the other hand, grades their AI detection to have 98% accuracy. Even so, Mr. Shay, an English teacher, says that his “mindset towards originality is starting to return to what it was like before we started using Turnitin.”

Three of the teachers who responded to my survey reported having a student use AI on a class assignment that they were aware of. One of those teachers is Mrs. Umstead. “It is making me question myself as a teacher. I feel like I know my students’ writing, but this had made me question that fact. The AI writing I have seen looks very similar to what a junior in high school might write, so who is to know? I definitely check editing histories much more than I ever have before.” She goes on to say, “ It is easy to assume that students are being deceitful by using AI as a cheating option. We need to be diligent about making plagiarism rules very clear and understandable to students.”

Currently, the Integrity Policy of the Student Handbook at DCHS reads, “DCHS defines cheating as using someone else’s words, work, and/or ideas, and claiming them as your own.” Dr. Arnold explains that the use of AI is not explicitly prohibited, but it is inherently a violation of the Integrity Policy because it is still copying work.

AI regulations are being enacted in other domains too. Mr. Sheaff, Director of Drama and Debate at DCHS, shares that the National Speech and Debate Association has already stipulated new rules around AI material. Sundar Pichai, the head of Google, calls for governments to make uniform treaties that reflect universal human morals. One way that institutions are already monitoring the use of AI is by incorporating watermarks to easily recognize it.

An area where the use of AI weighs especially heavily on the mind of educators is in regard to college admissions. After reaching out to Mrs. Koppes, the College and Career Coordinator at DCHS, she explained that college admission counselors search for personalized essays that distinguish students from the pool of other applications. “AI technology in my opinion is a double edge sword. On one hand, AI tools can help students receive constructive feedback and edit their texts. On the other hand, I can see these tools being abused to create impersonal and overly polished essays. “

In light of the growth of AI, she foresees colleges placing more value on personal interviews during the admissions process, which she says “may reveal discrepancies between the excellence of an applicant’s written materials and their verbal communication abilities, or it may confirm how stellar of a candidate they really are.” She could also see a video submission as a way for colleges to better interpret a student’s voice.

Ultimately, the use of AI comes down to trust. College admissions counselors must trust that the teachers are instilling the importance of self-thinking and problem solving in their students, the teachers must trust the students to prioritize cognitive development over checking items off of a to-do list, and students must trust in their abilities.

Otherwise, if this cycle of trust is not achieved and AI is used as a source for answers rather than a guide for research, “the learning part doesn’t take place,” Mrs. Kane reiterates, “unless you count learning how to cheat as learning.” Today, Mr. Flood observes that “students tend to do one Google search and become discouraged if a spectacular, nuanced answer isn’t delivered on the first go.” He cautions that “as technology usurps a need to understand a skill (navigation apps for example), you become reliant on that tool instead of being able to produce it yourself.”

When I think back on my reliance on technology, I look at its integration into my school day. In first grade, I remember that we were only allowed to use iPads during indoor recess, and even then we were advised not to use apps with popular games like Talking Tom Cat, which responded to voice commands. By third grade, all of my classmates and I had our own Chromebooks, but they were often left unused in charging docks. It was not until fourth and fifth grade that the use of computers was a daily routine, largely due to assignments being completed electronically on Google Classroom instead of being done on paper. Once I got to middle school, students were allowed to bring their Chromebooks home, which motivated a new dependency on technology, one that drastically spiked with the at home and hybrid learning during the pandemic.

Through my eyes, AI prompts deeper introspection about individual and educational standards. Just this year, I have been in a classroom where my teacher accused us, the students, of not being able to think for ourselves. I think the reason I remember this remark is because it is true. At least in some ways. We are told that it is okay to fail…as long as we try again, as long as we make progress, as long as we eventually succeed.

While learning and growing shape an individual’s character, and therefore should be the priority in education, it often seems to get overshadowed by the prospect of achievement. Today’s students feel the pressure to learn and achieve. So, why risk failing, at least on problems that require nothing more than rote memorization, if we can guarantee that we’ll get the right answer and the “right” grade simply by pulling up an answer key, or, now, asking an AI chatbot?

AI is going to change the way we learn. Educators will need to re-evaluate what students need to know, perhaps shifting the emphasis from what to why. Students also hold responsibilities as schools adapt to AI. They will have to ask themselves if they will use their minds for expression and reflection or become a puppet for AI.

If students continue to rely on AI as a crutch, they will earn grades that will remain empty numbers, unless they choose to make their education more than a mere statistic. Students can use AI to get the percentage they want on a test and an acceptance letter from their dream college, but if they are unable to think for themselves, what is the point?

Mr. Shay says it best, “I think a significant percentage of students will not be as likely to challenge themselves and they will, as a result, not be forced to hone critical thinking skills as much as they have in the past. This does not apply to all students. Education is a choice. I believe that real student growth becomes more of a student’s decision.”

AI is here, and whether we embrace it or not, the future of our education is our choice.