“School used to be fun and a light-hearted place. Now, school can sometimes feel like sadness that lingers around.” The feelings of Perry High School Senior Class President Kaitlyn Delp-Leber come with the aftermath of a deadly school shooting that took place on the first day of second semester.

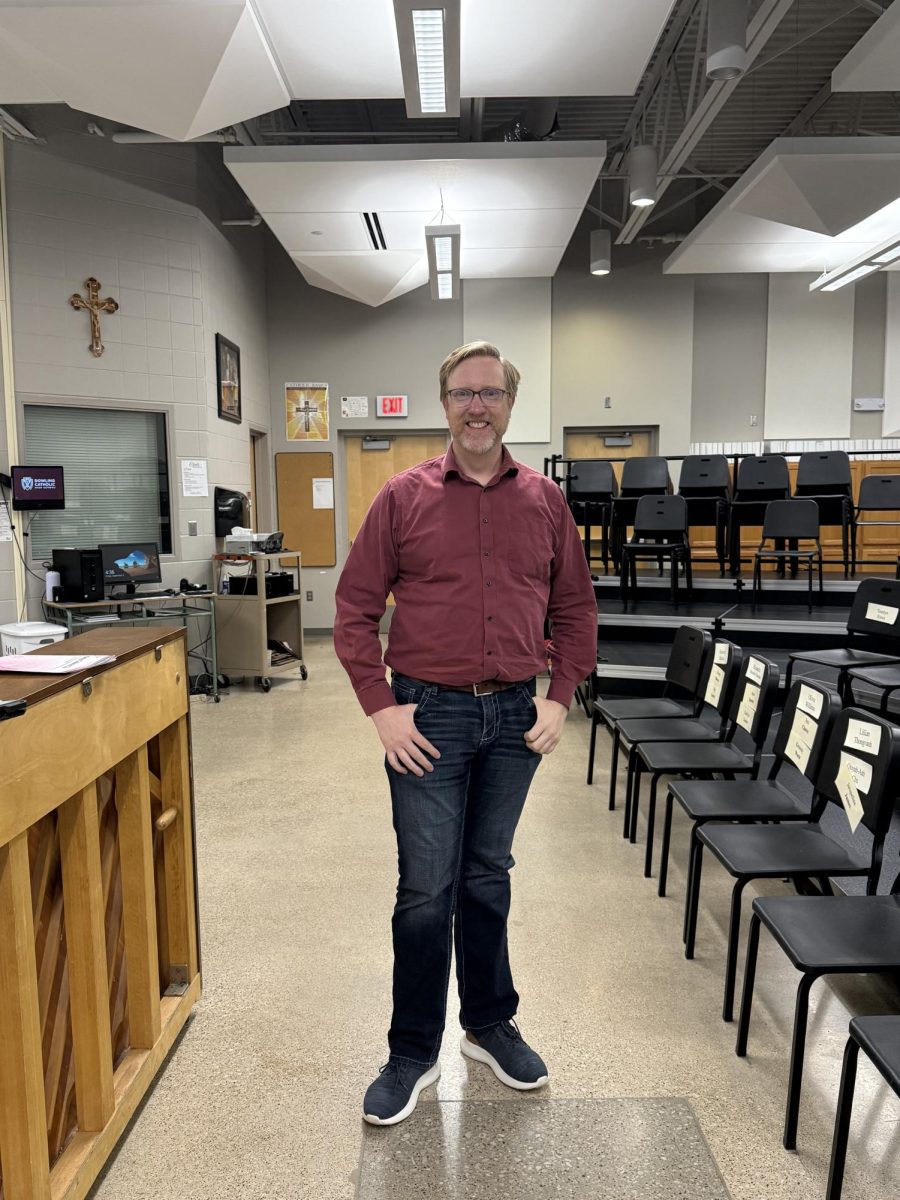

Similar to the lingering sadness described by Delp-Leber, Dowling Catholic teacher Jacqueline Pose notes the lingering fear she feels towards school shootings today. “I don’t think there is a teacher out there who hasn’t thought about their course of action if something were to happen; the threat of school shootings is something that feels ever-present and lingering.”

Before teaching at Dowling Catholic, Pose was a student at the high school from the class of 2016. She reflects, “Many of my friends and I felt like something like school shootings ‘couldn’t’ or wouldn’t happen at a school like Dowling because it was such a small, tight-knit, supportive community.” She adds, “Now that I’m a teacher and am watching constant instances of gun violence unfold both across the nation and within our own state, I’m not so sure that I believe that.”

Two months after the Perry High School shooting, Delp-Leber is a survivor of the gun violence that Pose and all Americans witness, whether first-handedly or second-handedly. Thirty miles away from Dowling Catholic, Delp-Leber praises her supportive community in Perry which has provided access to therapy dogs, free meals at restaurants, admission into movie theaters free of charge, and patience as her school plans to return back to full-time classes after spring break. “I couldn’t be more proud to live in such a caring community, and I still put my trust within my school.”

Soon, added trust may be put in school employees, like Pose, with the passing of House File 2586. As of March 6, the bill, which according to Senator Brad Zaun would “force insurance carriers to offer coverage to school districts that allow teachers to have a firearm with proper training,” was recommended to pass by its subcommittee and will now be debated by the Senate.

If made into a law, House File 2586 would not be the first piece of Iowa legislation to encourage armed school employees. In December, Section 724.4B of the Iowa Code made it legal for school employees with a permit to carry weapons on school grounds. To obtain this permit, employees over the age of eighteen need to meet requirements that include no former convictions, no history of repeated acts of violence, no records of substance addiction, and a “good moral character.”

House File 2586 builds on this law, granting school employees qualified immunity in cases of reasonable force which protects them from lawsuits. By doing so, it decreases a school’s liability and in turn, encourages insurance providers to cover school districts with armed employees.

The bill comes after a failed attempt to pass a different law last year which would have barred insurance providers from denying coverage to school districts based on their decision to arm employees, something the Spirit Lake and Cherokee school districts experienced when EMC Insurance declined coverage ahead of the 2023-24 school year if the schools proceeded with their plans to train and arm ten employees with handguns.

Representative Beth Wessel-Kroeschell spoke about House File 2586 to the Des Moines Register, saying that “this bill may take away or reduce the risk to an insurance company through qualified immunity, however, it does not reduce the risk to the student. This bill puts more children in the line of fire, and nothing is more frightening.” In an interview with Iowa Public Radio, she went on to say, “This bill reduces the risk for insurance and raises the risk to students and their families. If they are hurt or killed in crossfire, no one will be held accountable.”

Senate candidate Matt Blake echoes the potential consequences of the bill. “In a crisis situation with an active shooter, I fear law enforcement may not be able to identify between who is friendly and who is not. What happens when there are accidental discharges? Weapons left in the open or a bathroom? What are the standards for maintaining these weapons and training for teachers? As a Soldier,” Blake adds, “I understand the high standards necessary for maintaining firearms as a profession. Instead of arming teachers, we should be having conversations about further gun control measures. Students should feel free of fear of gun violence in their schools. Introducing more firearms does not meet that goal.”

The last part of House File 2586 requires school districts with 8,000 students or more to employ a private security officer or school resource officer in buildings that hold 9th-12th graders unless the school board votes against it. Both the armed school employees and security officers would be required to undergo live scenario and firearm training with the Department of Public Safety.

The Fiscal Services Division concluded that forty buildings across eleven school districts would qualify for the requirement to employ an officer, and through the School Security Personnel Grant Program, school districts could apply for $50,000 per 9-12th grade building “to offset costs associated with employing, or retaining the services of, a private school security officer or school resource officer,” a cost estimated to be an average of $63,000.

Currently, Dowling Catholic employs a full-time School Resource Officer on campus, and “because of this factor” Dowling Catholic President Dr. Dan Ryan says, “we do not envision other employees being equipped with a firearm on campus.”

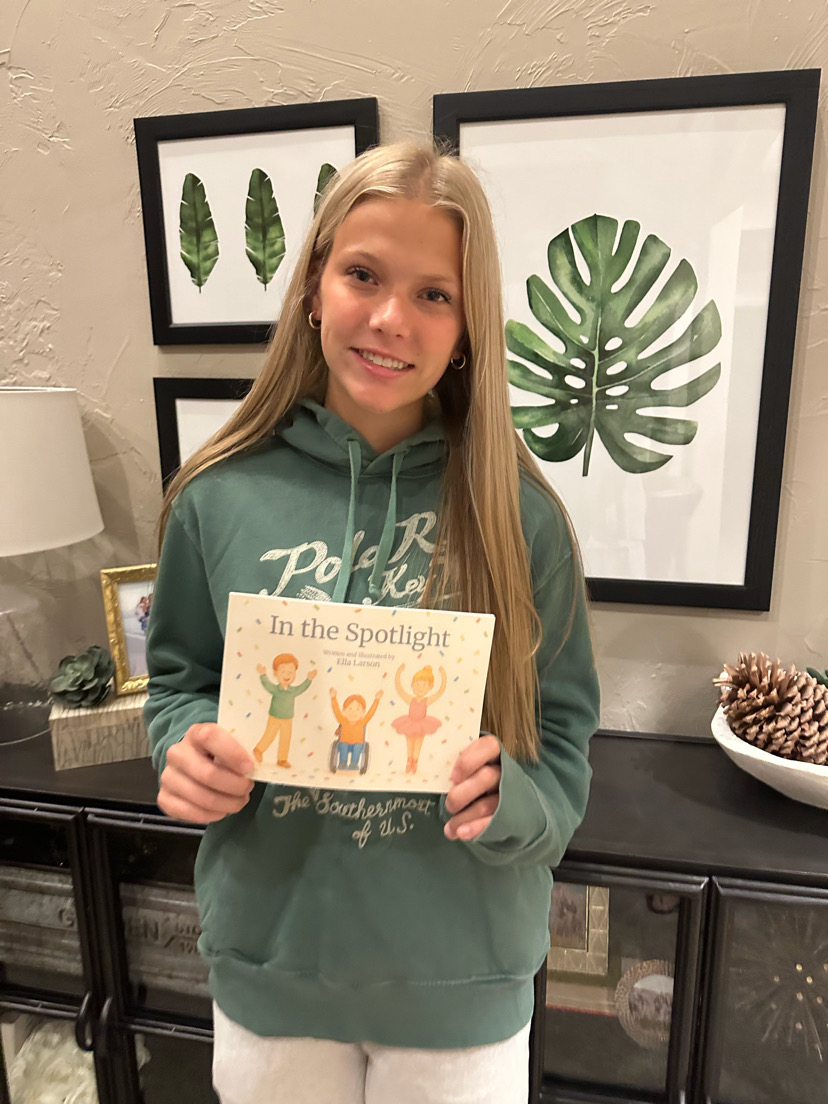

Jolenne Bigelow, a freshman at Dowling Catholic, recognizes the proactive safety measures at her school. “Luckily I go to a school where safety is the utmost priority.” That said, Bigelow went on to share that “the possibility of a shooting haunts every school and every student in America.”

Last summer, Bigelow attended a summer program in Cambridge, England, and came to the stark realization of how gun violence has become a feature of American culture. “We were talking at lunch about differences in where we live when my friend from Scotland brought up school shootings in the U.S. With a concerned face, she asked me if I had ever experienced one. I was fortunate enough to be able to say no, but it sparked a conversation about the U.S. and the horrifying fact that school shootings are something our country is known for. My friend told me that it sounded terrifying and she could never imagine that happening to her. I told her that my dad is a math teacher at a high school and every day I am concerned for both his life and the lives of me and my sisters.”

Bigelow’s conversation became a turning point for her. “My friend’s shock and concern really made me realize that the way school shootings are treated in America is not normal and is not okay. Lives are in jeopardy and these tragedies keep happening.”

When Hannah Hayes was a sophomore at Roosevelt High School, a shooting at a prom after party was the turning point in her fight to end gun violence. “I saw so many of my friends reposting things on Instagram demanding change, but I didn’t see anyone actually taking action.”

In the wake of social media, not taking effective action against gun violence is increasingly convenient. The idea of “performative activism” centers around saying or showing one’s support instead of doing. For example, by simply clicking “like” or “repost,” an individual often feels personal satisfaction with their effort to campaign for justice and garners social capital for publicizing their support, but in reality, the issue remains unchanged.

Author of The Democratic Ethos Freya Thimsen suggests that performative activism habits require, well, more performance; action that extends beyond “social media posts and progressive advertising themes” and does not stop with thoughts and prayers.

To change how one advocates for change, Thimsen offers three questions:

- Are you really trying to understand the issues?

- Have you really done the work of understanding your own privilege?

- Are you talking to people about these things in real life?

Finally, she offers a directive: “Educate yourself.”

After observing her peers’ performative activism in the shadow of Roosevelt’s post-prom shooting, Hayes asked herself these questions and took a stand to do more. “I decided to hold a walkout for my school and soon got in touch with March for Our Lives after that. I served as the organizing director last year and am currently the co-executive director.”

March for Our Lives is a national youth-led anti-gun violence movement created after the Parkland, Florida, school shooting. “We have planned walkouts, protests, lobbying days, panels, and published an op-ed so far this year,” says Hayes, “but we are just getting started!”

Hayes encourages fellow high schoolers to join in the fight against gun violence by contacting March for Our Lives organizers (listed on their website or email [email protected]) to receive resources on how to start a March for Our Lives chapter at their school.

She is an embodiment of the impactful change youth can make, both to stop gun violence or to incite any political, social, or economic reform for the common good. “It is absolutely critical for youth to get involved in politics because youth are the future,” Hayes continues, “Without the youth voice and vote, there is no future. We must use our voices to advocate for the change we want to see. We hold the moral high ground in these matters and our perspectives are incredibly valuable and impactful. Specifically, as youth we face the harsh realities of gun violence each day we go to school and put ourselves at risk of a massacre. Because this issue impacts us so personally, we should be providing our insights every chance we get.”

Anisha Choudhary, one of the one hundred students in the Iowa Youth Congress, actively provides her insight on the Permitted Civic Engagement Absences Committee, where her team wrote a bill that proposed a simpler avenue to youth participation in events like town hall meetings, candidate speeches, campaigns, or poll working.

“We chose to write this bill because we get the opportunity to participate in civic events a lot, however, the burden of missing school and having makeup work is very discouraging.” Correspondingly, Choudhary explains that “the bill requires school districts to permit students with one excused absence per school year to attend civic events.”

Choudhary and her committee presented their bill to the state legislature during a Mock Congress and were sponsored by Representative Art Staed and Senator Molly Donahue. While the bill later died after not being scheduled for a subcommittee meeting, it can be reintroduced during the next legislative session. “Nonetheless,” Choudhary says about her time in the House Chamber, “It gave us great hands-on experience, and I am so grateful for the opportunity to work with our state legislators!”

Whether as co-directors of political movements or members of youth congress, today’s youth do not have to wait until the legal voting age to make waves in America’s political climate. Change begins with awareness, and the haunting aftermath of school shootings at Perry High School and the pervasive fear of gun violence in schools like Dowling Catholic echo a sobering truth. As debates over arming school staff intensify, the work of Hayes and Choudhary underscore the imperative for meaningful action and honest dialogue that aims to prevent gun violence in educational environments and develop a youth perspective in politics, so that future generations will not walk into school each day with a lingering sadness or fear; will not have to see social media posts mourning the latest school shooting; will not have to write articles about efforts to end it.