“I miss the days when five or six students would raise their hands in class.”

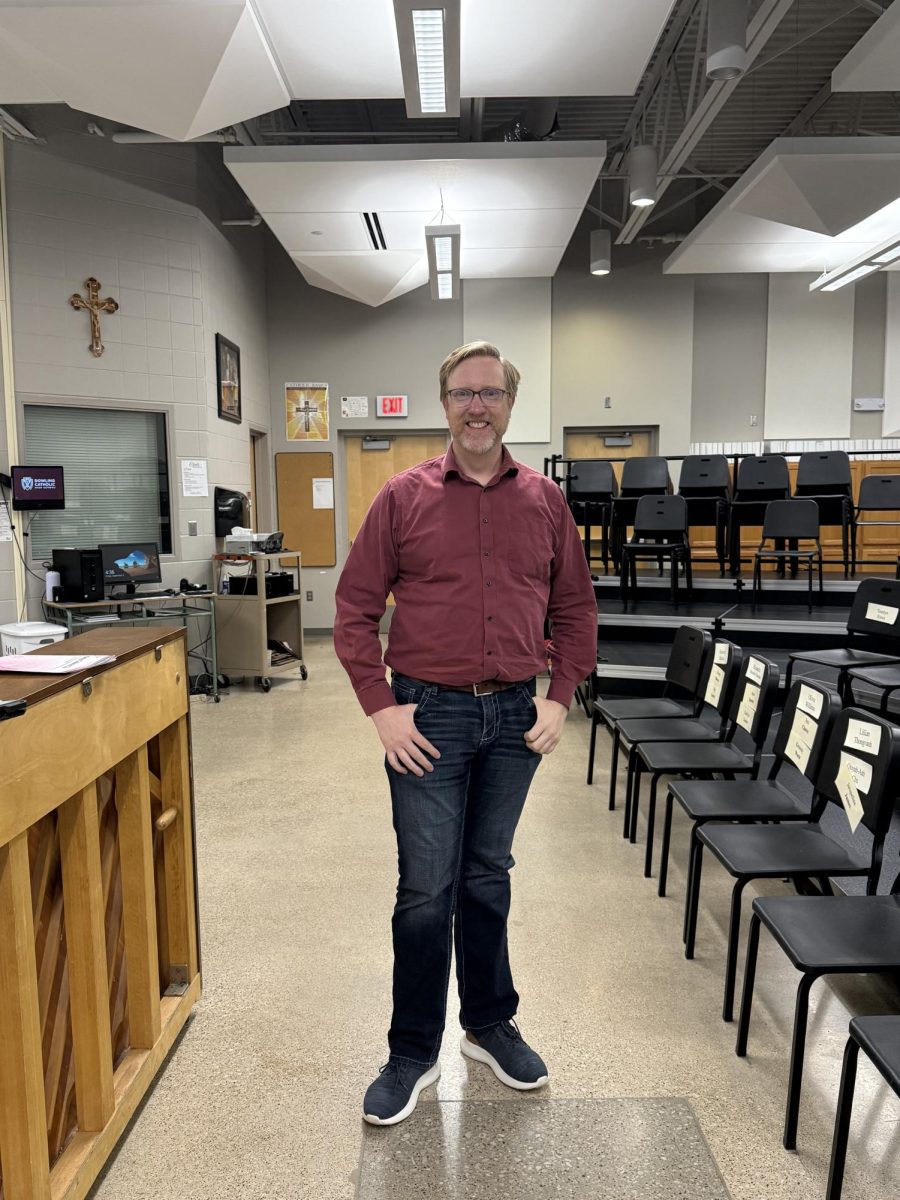

Mrs. Diane Thierer of Dowling Catholic does not only teach senior level theology courses like Comparative Christianities and World Religions; she is also teaching her students how to talk about their differences.

“I think because we’re talking in a theology class, hopefully, people aren’t afraid to ask questions about their own faith but about others as well. Especially in Comparative Chrisitantities and World Religions, students are studying things that maybe they don’t know about, so it’s more natural to ask questions, and I encourage it as much as possible.”

As seniors, many of Thierer’s students are in or on the brink of adulthood, where it can feel trivial to be tasked with classroom activities like a three-minute conversation with the person beside you. But, perhaps it is precisely at this age, with adult responsibilities such as voting and planning their looming futures, that prompts the revisiting and refining of communication skills.

The need to practice talking has been especially essential upon the return to classrooms during the pandemic. Five years from the emergence of COVID-19, and its reverberations are still being felt. Back in November 2020, as schools navigated the return to classrooms, EdWeek Research Center published survey findings that over 80% of teachers reported a decline in student motivation and engagement since the pandemic.

Thierer believes the reluctance for students to participate in her class may similarly be rooted in the pandemic, terming the disengagement, “residue from covid.”

“There was quiet, careful talking because people didn’t want to get too close to you, even with masks on. Nobody wanted to break the ice.” Thierer also notes that safety logistics like students being confined to specific seats for the purpose of contact-tracing further contributed to students’ discomfort in starting conversations with one another.

Today, while no longer needing to adhere to pandemic protocols, Thierer recognizes how the pandemic created a discomfort in talking to others that has now grown into a lack of confidence, made evident by a reliance on technology and an added “fear factor” in being incorrect.

One way Thierer is moving back to the days when students shot their hands into the air is by exposing her theology classes to different ideas that they may or may not be comfortable with.

She recalls a World Religions student years ago who came to Thierer one day, saying, “I’m in some trouble. I told my dad that we’re studying Islam, and I brought my book home, and he is so anti-muslim that he just refuses to believe they’re good people.”

With 90% of Dowling Catholic students identifying as Catholic, it can be easy to push away the otherness seen in different religions. Even so, Thierer challenges students to dismantle both internal and external biases, encouraging them to form their own opinions rather than passively inheriting prejudices. The same student whose father couldn’t see the humanity in other religions told Thierer, “I’m going to hold my ground,” a testament to how the lessons taught in Thierer’s classroom aren’t just about religion, they’re about developing empathy and equipping students to navigate a divided world with confidence and conviction.

“Your opinion might differ from your parents’ opinion—and that’s okay. You’re a young adult; you can think on your own.” By nurturing these skills in students, she hopes to prepare them for a future where dialogue bridges divides rather than deepens them.

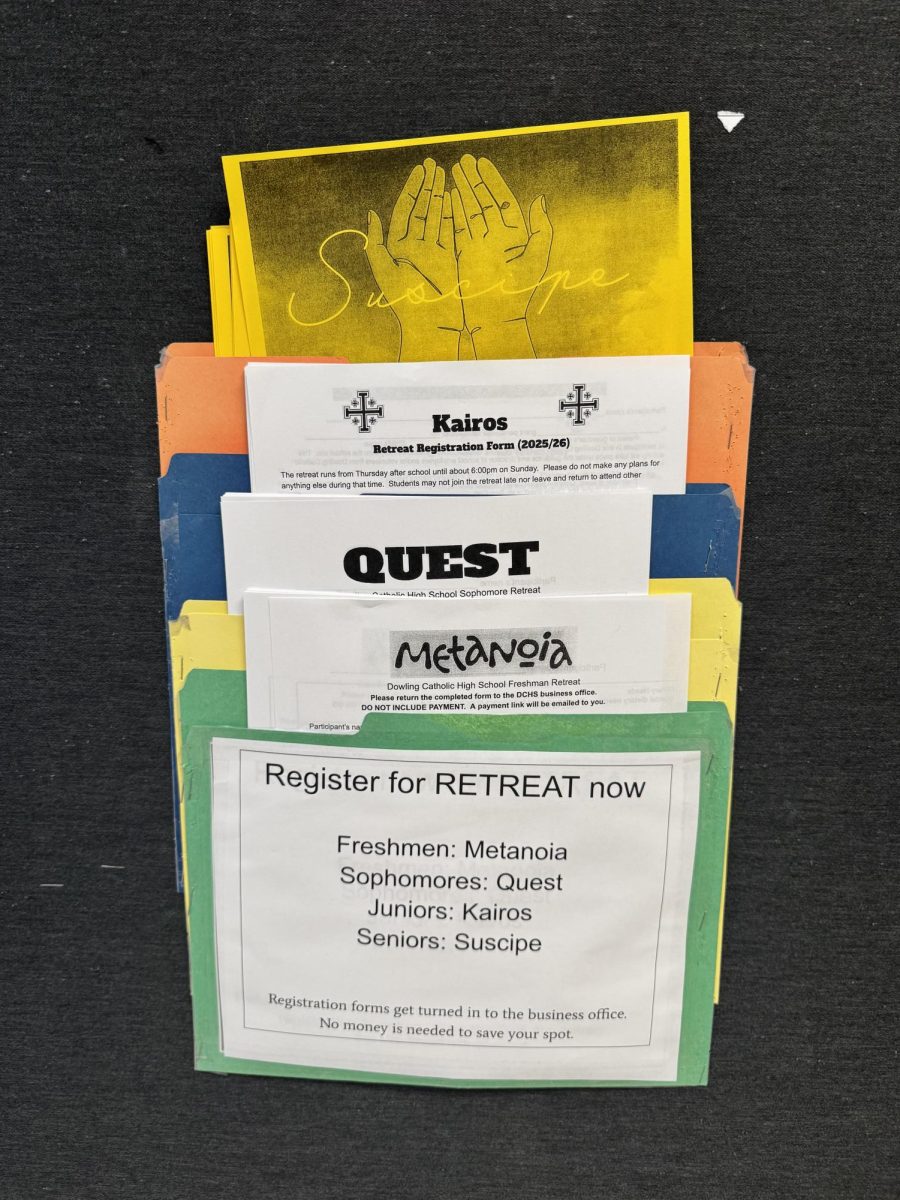

At the beginning of November, Thierer traveled with fellow Dowling Catholic theology teacher, Mr. Terry Clark, and their students to visit a Sikh Gurdwara at The Iowa Sikh Association in West Des Moines. Thierer says interacting with those practicing a different religion and being able to ask them to explain their life experiences “strikes our curiosity.”

During the field trip, students learned about the tenets of Sikhism, viewed the sacred text called the Guru Granth Sahib, participated in a meditation, had the opportunity to wear a turban, and were generously treated to a langar, which is the communal meal shared by Sikhs and all visitors to a Gurdwara.

Ajoung Ajoung, a senior in Thierer’s World Religions class, reflects on his time at the Gurdwara: “I found it so beautiful to learn about the many similarities between Sikhism and Christianity. It was memorable, and I encourage everyone to take World Religions so that they can experience it too.”

Once again, exposure to and discussion of differences prompted an appreciation for a common denominator. “It just removes so much angst between people if someone can say, ‘I feel this way because of my life experience,’ which someone else may not know anything about. Not just your generation but older generations and younger generations—we have to find some common talking ground again and not be fearful.”

For Thierer, these moments of connection and discovery fuel her optimism. “I thrive on the classroom interaction,” she says, “that’s what gets me to school everyday.” Because in a world that often feels irreparably divided, every raised hand, every question asked, and every opinion shared is a reminder that her classroom isn’t just a place to learn—it’s where the future learns to talk and listen to each other.